How did a tiny, isolated nation reshape itself into a major hub of the entertainment industry overnight and the refuge for actors and singers in search of a fanbase? Thank the “Big Five,” oh, and Gunsmoke. In the late ’50s, Japanese entertainment was a mess, with competing companies and unions all fighting each other and themselves. The folks purchasing TVs quickly found there wasn’t much on, a problem created by the five largest movie studios. You think show biz is sordid now? 70 years ago, Japanese film studios fought a literal gang war, extorting their employees all in a bid to cripple television networks. TV won.

Their master plan had peculiar repercussions. The expression “Big in Japan” is typically a back-handed compliment, springing up in the English-speaking media in the ’70s to describe bands or actors who can only find lasting adoration in Japan, not at home, best exemplified by the fictional band Spinal Tap. The origin is murky, but we can trace back the exact year and reason the Big in Japan trope came into existence. The glut of foreign television flooding into Japan showcased different types of genres, cinematic styles, and acting/writing techniques, naturally a great opportunity to study and analyze Hollywood, and some of the content the viewers gravitated toward defied explanation.

Substituting the English lines of dialogue, the new versions were broadcast throughout the nation for decades, a staple for curious audiences who had little understanding of the Old West or Midwestern suburbs. These strange broadcasts fulfilled the same kind of exotic fantasy as samurai movies did in the West, or served to advertise the luxurious lifestyle synonymous with the American Dream. Within a short time span, US reruns became prestige viewing like HBO, the production value of American shows unmatched at the time, regardless if they weren’t all huge hits back in the States.

Japan’s Appetite for Western Entertainment

Japan in the ’40s is a culture that Miyazaki fans, Ōshima aficionados, and manga lovers wouldn’t recognize. In comparison to the varied, acclaimed films they would produce in the latter half of the 20th century, the output in the first half was lackluster. Look at any critics’ list of the best Japanese films, and you will rarely find a film made prior to 1949. Japanese companies didn’t afford the same freedom, scale, or ambition as their counterparts, discouraging special effects, boundary-pushing themes, goofball comedies, and kaiju monsters.

The biggest repressed influence seemed to be focused on animation. American cartoons leaked into the country little by little. Japan’s deep affection for Western media (mainstream or otherwise) dates all the way back to before WWII. But the war was the turning point that allowed the floodgates to open. Fantasia, an ambitious film that flopped hard at home — to Walt Disney’s great irritation — was beloved across the Pacific. According to author Matt Alt in Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World, it stirred many animators and writers:

“In 1941, the imperial military screened a copy of Fantasia , discovered aboard a captured American transport ship, for propaganda filmmakers. The idea was that they might better know the enemy. It seems to have worked. One of the men in attendance was so moved by its craftsmanship that he burst into tears at the finale.”

Regardless of the fondness the Japanese possessed for Disney films, Donald Duck comics, or Raymond Chandler novels, this stuff wasn’t that easy to obtain. And there was no way whatsoever to see US television for years. That would change in a blink of an eye, thanks to one short-sighted decision.

The Failed Conspiracy to Kill Network TV

In just three years since the first TV networks launched, the battle for viewers reached critical mass. Without any objective rating-gathering tool or metric to measure, each network boasted that it had the best viewership. The networks were probably lying about their unbridled success (as opposed to modern streamers who hide their viewing statistics), but the movie tycoons — smug after a string of international hits — took the bait.

The studios had been engaging in shady practices for decades. Matters got so out of hand that one studio hired a mobster to disfigure heartthrob Kazuo Hasegawa’s face when he joined a rival film company during the ’30s. To prevent studios from stealing each other’s acting talent, and to starve their rivals in the television industry out of content and bankable celebrities, the five largest film companies (Daiei, Shin Toho, Shochiku, Toei, and Toho) held a meeting in 1956, per NHK. A sixth company would fall in line a couple of years later, agreeing to boycott TV, sending a clear signal. It remains unclear whether any of these shenanigans were ever legal. Incidentally, this is why centralized power and monopolies are terrible for artists and consumers.

Referred to as the Five Company Agreement, none of the participating studios who met in that smoky room would allow their films nor contracted acting talent to ever appear on TV at the risk of being blackballed. To make up for the shortfall on their slate of now vacated time slots, TV programming heads opted to contact American distributors for help. A year later, Japan was inundated with US hits, I Love Lucy being one of the first proofs of concept aired, followed by more niche programming like The Twilight Zone. In a reversal of fortunes, Japanese movies were losing money internationally by the seventies, a shell of their former glory, while the networks were chugging on.

How Cowboys, Superheroes, Gangsters, and Housewives Took Over Japanese Airwaves

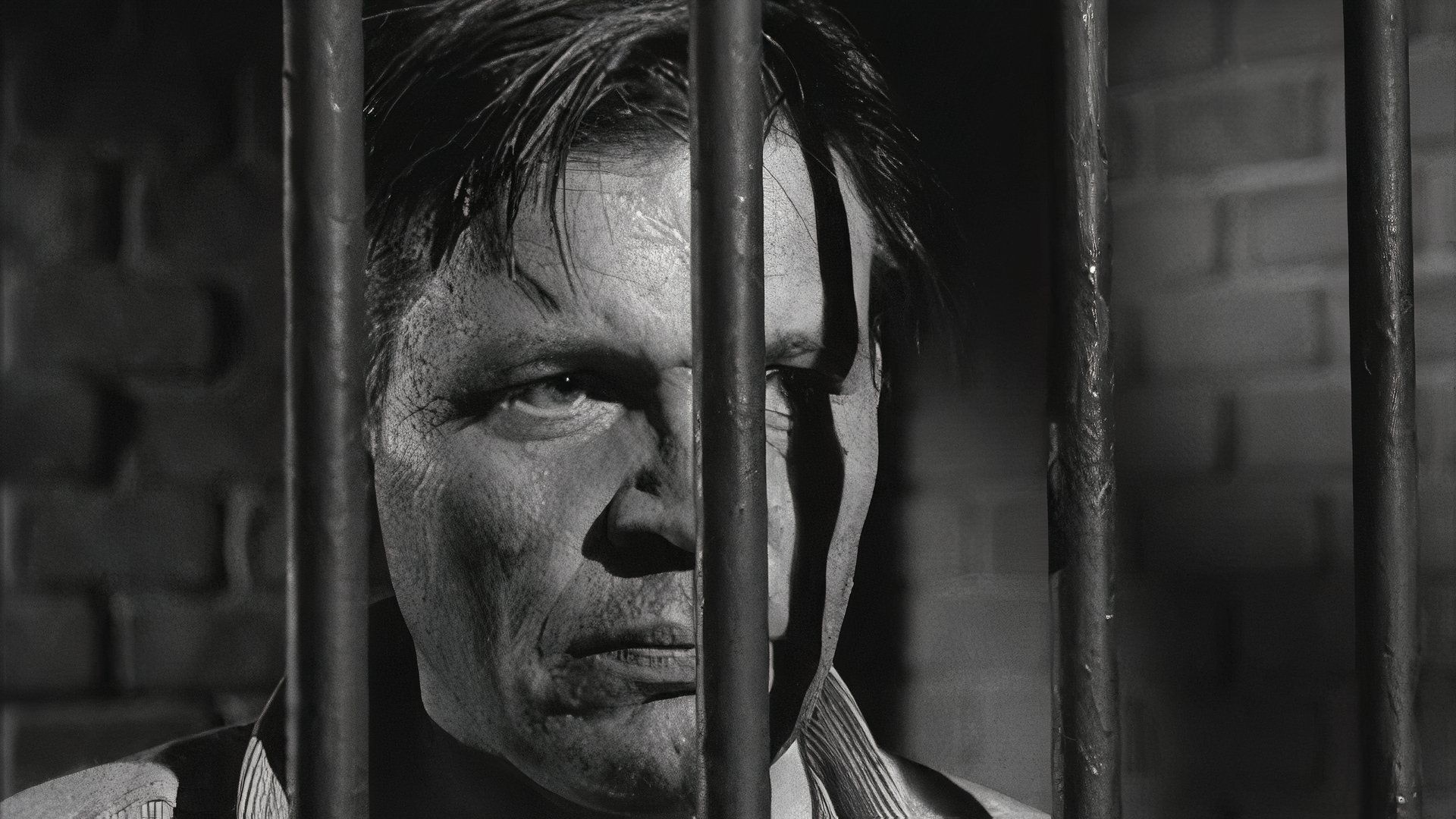

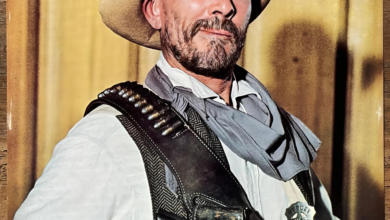

1964 marked the apex of the artistic subjugation of Japan, author Bruce Stronach of Beyond the Rising Sun notes. One of the most mentioned Japanifed pieces of American pop culture from accounts from the ’60s was the long-running western starring James Arness, CBS’s Gunsmoke. A few of the other recognizable syndicated shows that found a new fanbase abroad included: The Untouchables, Father Knows Best, The Lone Ranger, Perry Mason, Superman, Lassie, 77 Sunset Strip, The Donna Reed Show, and Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Japanese audiences had their own tastes. Two Westerns in particular proved to be huge ratings winners with Japanese viewers, outperforming the venerable Gunsmoke. Rawhide had an awesome 35 share of its time slot. Terrific as those numbers were, it was outdone by Laramie, which claimed more than 40 percent of all viewers in its slot, or so the networks asserted.

In some cases, Japanese producers staged their own fake American sitcoms, casting white, US-born performers who spoke in Japanese rather than being awkwardly dubbed.Tokyo Blue Eyes Diary is one well-known example of reverse engineering a facsimile. It’s faithful down to pro-American themes, patriarchal social cues, and transparent lifestyle branding–the show sponsored by a dairy company, a novelty to readers when it appeared in a 1959 issue of The Saturday Evening Post:

“Although calculated to sell cheese, it has also helped sell America, in that has brought Americans and Japanese closer together. And it hasn’t cost the United States taxpayer one cent.”

The once-ominous Five Company Agreement crumbled as the movie studios fell on hard times, yet the consequences reverberate. In the grand scheme of things, the incident was a net positive for Japan and the world, as actors and singers found new markets, and consumers discovered new entertainment. Obscure films like Disney’s Rascal still retain some popularity in Japan a half-century later, perhaps the ultimate big-in-Japan-and-unknown-everywhere-else case study. Not to be outdone, Americans eagerly import Japanese anime and live-action TV programs (Super Sentai and Takeshi’s Castle both redubbed and re-edited for American sensibilities as Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and Most Extreme Elimination Challenge), as cultural exchange came full circle.